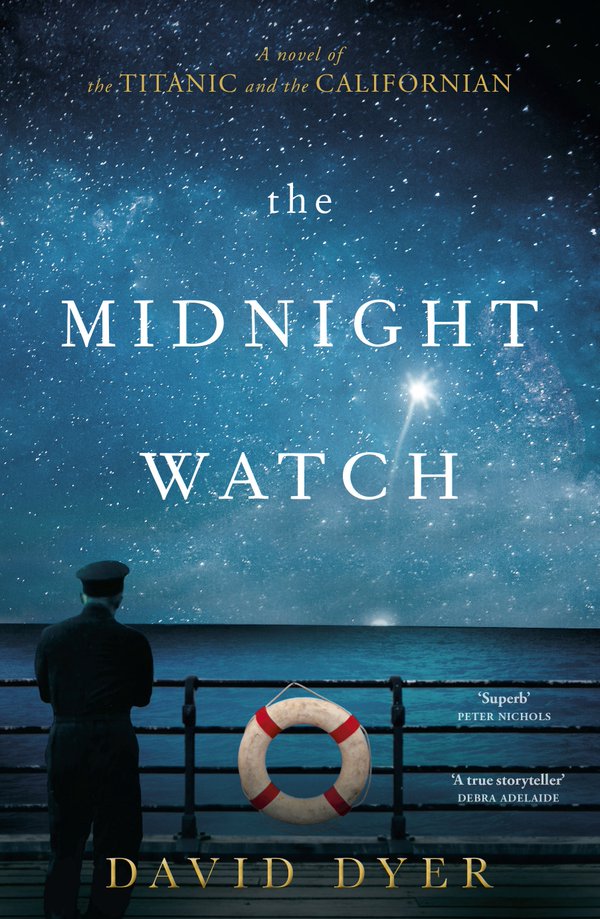

Title: The Midnight Watch

Author: David Dyer

Genre: Historical Fiction

ISBN: 9781250080936

Published: April 5, 2016 St. Martin’s Press

Purchase: Amazon, Barnes & Noble

Main Characters: John Steadman, Stanley Lord, Herbert Stone

Synopsis: Did you know that on the night of April 14, 1912, when the Titanic was sinking, that there was a large cargo ship six miles away that could have saved every person who died that night? Boston reporter John Steadman, covering the horrors of that night, learns about the ship and its complete inaction. Unlike the other reporters, he is not content to let it stand. Thinking of the twelve hundred people who died that night (including fifty-three children, whose names no one can be bothered to utter), he dons disguises and travels thousands of miles to uncover the truth: How could the SS Californian see every one of Titanic’s eight distress rockets and do nothing? The Midnight Watch by David Dyer, based on actual articles and dispositions of the time, aims to delve into the mind of those responsible and find out the truth.

Check out the review behind the jump!

Excerpt

‘You think Captain Lord was a hero?’

‘Of course. A tragic hero, because he didn’t get there in time, but a hero nonetheless.’

I paused. Thomas tried to encourage me. ‘Don’t write it for me, old boy,’ he said, ‘or even for IMM. Write it for England. Write it for America. Write it in defence of manhood across the world.’

‘What do you care of manhood?’

‘Whatever do you mean? I am a great fan of manhood.’

‘Well – boyhood, perhaps.’

‘Let me buy you another drink, John. I can tell you’re in one of your moods.’

He was right. I was tired and fractious. I hadn’t been sleeping properly. Nor had I seen my daughter since I returned from New York, and without her laughter and energy I soon became dissipated and flat. The tavern seemed airless; there were too few customers and too many dogs. The sawdust smelt of urine. I could hear bar girls, short of tips, arguing in a distant room. And although I liked Thomas, this afternoon, as he sat opposite me trying to get the attention of a waitress, he seemed particularly repulsive. He had rubbed cooking oil into his face to give himself a youthful sheen. His white suit, smeared with coaldust and ink, was too tight. A steamy heat rose from his lap.

But it was the story in the Globe that had angered me. In six columns over two pages it described in great detail the deeds of brave men, but I had not seen one word about any of the children who died.

Because by now we knew the numbers. Fifty-eight first-class men had found their way into the lifeboats but fifty-three third-class children had not. It was an almost perfect one-for-one correlation. For almost every rich man who lived a poor child had died. How had this happened on a ship that took nearly three hours to sink in calm water? What sort of tale of heroism was this? Was this the story of America? I remembered the fuss Watch and Ward had made about me using my daughter to pose as a child prostitute on North Street. They bleated and complained and tried to have my story banned, but what had they said about the fat men who’d tried to buy her? Nothing. And what now did they have to say about the dead children of the Titanic? Again, nothing. If only those children’s little bodies had been in the hold of the Californian, I could have written about them and made them live long in Boston’s conscience.

Review

John Steadman is no one’s hero. For decades, his wife Olive has blamed him for the death of their infant son; suffering under that weight, he drinks much and swears more. He’s kind, though; he’d never lay a hand upon anyone, and he looks upon his teenage daughter, Harriet, with reverence and admiration. Olive and Harriet are knee-deep in the suffragette revolution, and he looks upon their adventures with a touch of whimsy, knowing this coming century will belong to the women.

John does have a quirk, though: he writes stories about dead people for the Boston American. He covered the losses in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, bringing not only the stories of those poor women to life but bringing ruin to the owner who hopped to a nearby building and escaped all flames. Tragedy has struck again in the northeast, this time in the form of an unsinkable ocean liner: the Titanic.

He’s headed up to New York to meet the ships that will be bringing back not only the survivors, but the dead as well. For that is what he does: he tells the stories of the dead.

However, a ship rolls into the harbor without any survivors, and controversy blooms before his very eyes. This ship, the SS Californian, was approximately six miles from the Titanic the entire night. Why in the name of heaven and hell did they not rush to its aid?

Captain Stanley Lord’s masterful coverup is a source of debate that has raged for over a hundred years. Even after appearing in maritime court in both the United States and England, being stripped of command, and being shunned the world over, he never backed down from maintaining his innocence, a position whose mantle his son took over even after Stanley’s death. Author David Dyer attempts to go inside the mind of this ice-cold, proud, powerful man and understand the rationale. One of the youngest captains ever appointed by the Marine Mercantile, Stanley Lord was no fool: he, along with his officers and deckmates, knew exactly what white rockets stood for. And yet, no one on the ship moved a muscle to aid the Titanic. Why? And how could one continue to live with himself after the news of their inaction had reached them?

Lord’s defense is littered with excuses, and only two men on the ship ever had the courage to speak out against him. Their accounts are what led to the subpoena, but the stoic resolve of the other officers leave no one out to dry, no one held accountable. The second officer, the one who saw the rockets and reported them to the captain, did not take control of the situation when the captain failed to act. The captain perhaps assumed that the second officer should have acted. As David writes, “So the responsibility for action fell like a snowflake from the sky, landing gently between them, touching neither. And in his concentrated moment in history, nothing was done. Those rockets! Unanswerable then and unanswerable ever after.”

For this blunder, you see, resulted in the single greatest preventable loss of life in human consciousness. Captain Lord maintained that he did not know that the rockets the Titanic fired were distress signals; perhaps they were company rockets, which were launched by ships to display their company line, or even celebratory rockets. (At midnight, you ask?) Even so, what is the harm in steaming over to find out? Having stopped for the night due to the abundance of icebergs, steaming toward the ship was a risk, but negligible and necessary by all maritime laws. It’s a risk the Carpathia took, even at great danger to all of its passengers. The Californian was a cargo ship.

Thoroughly researched and beautifully written, The Midnight Watch by David Dyer is a wonderful piece of historical fiction. I, for one, did not know anything about this second ship that watched from a distance and made no attempt to help. I’m not sure why this fact has never grazed pop culture’s consciousness, but there it is: it’s true. You can read the transcripts from the court hearings. Reports from Titanic survivors mention seeing the lights of this ship in the distance. The final tale John Steadman ends up writing about the disaster returns him to his roots: the stories of bodies. But the juxtaposition of the lies and pride of Lord’s courtroom against the story of a third-class family from Liverpool freezing to death makes it sing.

Do yourself a favor and pick this one up, and resolve to do better the next time you find yourself in a position to enact change.

Rating: ★★★★

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.